Key Points

-

Provides insight into the 'journey' taken by chronic orofacial pain patients through the healthcare setting.

-

Illustrates the potential for multiple different treatment modalities being employed with limited clinical success.

-

Emphasises the need for nationally standardised clear-cut care pathways for patients with chronic orofacial pain, in order to reduce multiple re-referrals and improve efficiency.

Abstract

Objective To gain a deeper understanding of the clinical journey taken by orofacial pain patients from initial presentation in primary care to treatment by oral and maxillofacial surgery.

Design Retrospective audit.

Sample and methods Data were collected from 101 consecutive patients suffering from chronic orofacial pain, attending oral and maxillofacial surgery clinics between 2009 and 2010. Once the patients were identified, information was drawn from their hospital records and referral letters, and a predesigned proforma was completed by a single examiner (EVB). Basic descriptive statistics and non-parametric inferential statistical techniques (Krushal-Wallis) were used to analyse the data.

Data and discussion Six definitive orofacial pain conditions were represented in the data set, 75% of which were temporomandibular disorders (TMD). Individuals within our study were treated in nine different hospital settings and were referred to 15 distinct specialties. The mean number of consultations received by the patients in our study across all care settings is seven (SD 5). The mean number of specialities that the subjects were assessed by was three (SD 1). The sample set had a total of 341 treatment attempts to manage their chronic orofacial pain conditions, of which only 83 (24%) of all the treatments attempted yielded a successful outcome.

Conclusion Improved education and remuneration for primary care practitioners as well as clear care pathways for patients with chronic orofacial pain should be established to reduce multiple re-referrals and improve efficiency of care. The creation of specialist regional centres for chronic orofacial pain may be considered to manage severe cases and drive evidence-based practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Chronic orofacial pain is a clinical term that encompasses several chronic pain conditions affecting the orofacial region including: persistent idiopathic facial pain, trigeminal neuralgia, burning mouth syndrome and some sub classifications of temporomandibular disorders (TMDs) to name but a few.1,2,3 Recent studies have shown that the prevalence of chronic orofacial pain of non-dental origin is 7%4 and that orofacial pain conditions can be difficult to diagnose and manage.1,5,6 Diagnosis is often only confirmed following assessment from a number of specialists in multiple fields, involving secondary and tertiary referrals,3 which can make the process protracted and potentially resource intensive.

Excluding trigeminal neuralgia, the evidence base for the management of some chronic orofacial pain conditions is somewhat lacking.7 This could potentially result in a lack of direction, leading to multiple treatment strategies being employed without a defined order7,8 and with limited success.9 In the current economic climate, budgets are subject to careful scrutiny and there may be costs in the current management pathways that could be reinvested in a different manner for management of chronic orofacial pain.

It is widely shown in research that patients with orofacial pain conditions demonstrate increased psychological distress, anxiety, depression and stress and are more likely to somatise.2,6,8,10,11 Many studies suggest that the psychological distress displayed by patients suffering from orofacial pain can influence the onset and progression of their condition11 and that early psychosocial management in patients suffering from orofacial pain conditions may therefore, have a positive influence on treatment outcome.2,11 It has been demonstrated in TMDs that numerous appointments with multiple specialties before diagnosis subjectively increases some patients' psychological distress and potentially contributes to the worsening of their complaint.12

It is therefore imperative that chronic orofacial pain conditions are diagnosed early, ideally in the primary care setting.1 Giving patients a name and explanation for their pain as opposed to referring them onwards without a (provisional) diagnostic 'label' may help to avert potential future psychological consequences.

The aim of this study was to retrospectively investigate the 'journey' taken by orofacial pain patients, from first presentation to treatment by the oral and maxillofacial surgical team.

Methodology

This was a retrospective audit registered with the appropriate institutional audit lead. Data were collected from 101 consecutive patients suffering from chronic orofacial pain, attending oral and maxillofacial surgery consultant clinics between 2009 and 2010. Chronic orofacial pain was defined as pain originating between the orbito-meatal line and the inferior border of the mandible, lasting for longer than three months.2

One author retrospectively completed a pre-designed proforma using the information available in the subject's hospital notes, which includes the correspondence about their case.

The proforma collected details on:

-

Demographics: age and gender, for the purpose of analysis, age was divided in to eight categories with 10-19-year-olds being the youngest group and 80-89-year-olds being the oldest group. The socioeconomic group of each subject was ascertained by using their post code from hospital notes and a free, publicly available website (www.upmystreet.com). The website 'upmystreet.com' builds a socioeconomic profile of local neighbourhoods, using a combination of government census data, land registry data and lifestyle surveys by CACI Limited. Information on the patients' employment status was also directly extracted from the patients' records where available

-

Referral, treatment history and treatment outcome: the patients' 'journey' through primary, secondary and tertiary care settings was examined in detail and recorded. Thus included the specialties consulted in relation to the orofacial pain condition, the treatment reportedly provided, its outcome and the current situation of the patient's orofacial pain condition.

It is important to note that in this study our use of the terms primary, secondary and tertiary care do not necessarily mirror how the NHS defines these care settings. Primary care is defined by the NHS as 'the activity of healthcare providers who are the first point of health system contact for patients who are based in the community rather than a hospital'.13 In this study the term 'primary care setting' is used to describe the patients' initial point of care: community- or hospital-based. General medical practitioners (GMP), general dental practitioners (GDP), accident and emergency (A&E) and dental emergency clinics (DEC) were all therefore classed as primary healthcare settings for the purposes of this study.

Secondary care is defined by the NHS as 'hospital or specialist care to which a patient is referred to from a primary care provider'14 and this was the same definition used in this study.

Tertiary care is defined by the NHS as 'the third and highly specialised stage of treatment, usually provided in a specialist hospital centre'.15 The use of the term 'tertiary care setting' in this study was allocated to any referral made from a secondary care provider to any further point of care within the hospital setting.

The current situation of the patients' orofacial pain conditions and the outcome of any reported treatment given were subjectively assessed by one author from the details in the patient's clinical records and allocated to one of four descriptive groups, shown in Table 1. Success of treatment was then also subjectively assessed by the same author and rated as per Table 1.

It should be noted that the figures for numbers of appointments and number of clinicians who assessed the subjects represent a minimum value. This is because where the number of consultations or the number of clinicians was unknown a simplifying assumption was used, allocating a figure of one, as the patient must have been seen at least once by a clinician in order to have received an onwards referral.

Simple descriptive statistics were calculated and a Kruskal-Wallis test used to investigate if there were significant differences in number of appointments and current status of orofacial pain condition.

Results

Full data from 101 subjects were included in the study. Six definitive orofacial pain conditions were represented in the data set: TMD, trigeminal neuralgia, neuropathic pain, burning mouth syndrome, temporal arteritis and atypical facial pain.

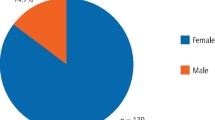

The majority (74%) of the sample were female. The mean age of the subjects was 47 years (SD = 16). Figure 1 shows the frequency distribution of the age bands by gender and Figure 2 demonstrates average income and education level estimated using web sources.

A minority of the cohort (7%) had no diagnosis recorded in their hospital records with 3% of the cohort awaiting the results of further investigations before the diagnosis could be confirmed. The vast majority of subjects (75%) had a diagnosis of temporomandibular disorder (TMD). Only 24% of diagnoses recorded as TMD were consistent with the sub-categories of the gold standard diagnostic tool, the research diagnostic criteria.16 The remaining 15% of the sample was made up of: trigeminal neuralgia (4%), neuropathic pain (4%), atypical facial pain (4%) temporal arteritis (2%) and burning mouth syndrome (1%).

Individuals within the study were treated in a total of nine different hospitals and were assessed in 15 distinct specialities: general medical practitioner (GMP), general dental practitioner (GDP), accident and emergency (A&E), dental emergency clinic (DEC), restorative dentistry, oral surgery (OS), oral and maxillofacial surgery (OMFS), ear, nose and throat (ENT), orthopaedics, oral medicine (OM), immunology, infectious diseases (ID), vascular surgery, psychology, and rheumatology. The mean number of consultations received by the patients in this study across all care settings was seven (SD 5). The mean number of consulting specialities was three (SD 1).

The mean number of consultations in the primary care setting and the mean number of clinicians who assessed the population in the primary care setting was one, although 21% of our subjects had accessed more than one primary care provider for help with their orofacial pain condition. For half of the sample (51%), there was no documentation of any attempted management of their orofacial pain condition in the primary care setting that could be gathered from referral letter(s) or in the initial secondary care history.

At the time of this audit patients had attended a mean of three appointments (SD 3) and seen a mean of two clinicians (SD 2) in the secondary care setting, for management of their complaint. A minority (17%) of the cohort had been assessed in more than one secondary care setting, having been referred to multiple secondary care providers for assessment and management of their single orofacial pain condition over time. For patients with multiple secondary care assessments the majority (88%) had been assessed by two secondary care providers, with the remainder (12%) having been assessed by three secondary care providers.

Tertiary care referral had been arranged for 32% of the cohort in order to manage their orofacial pain. Of these, the majority (81%) had been assessed by one tertiary care provider, 3% were assessed by two tertiary care providers and 16% were assessed by three tertiary care providers. The mean number of appointments in tertiary care was three (SD 3) and the mean number of clinicians our subjects were assessed by in the tertiary care setting was two (SD 1).

Table 2 shows the current status of the patients' complaints at the time of audit by the mean number of visits in each care sector. There was no significant difference (p >0.05, Kruskal-Wallis) between those with a better or worse outcome who had attended primary, secondary or tertiary care more or less frequently before referral.

During analysis of results it was noted that a number of subjects had repeated special investigations ordered by different specialities in order to investigate their orofacial pain condition. Table 3 shows the frequency of repeated investigations.

The sample had a total of 332 different treatment attempts to manage their chronic orofacial pain conditions and of those only 83 (25%) of all treatments attempted yielded a successful outcome. Tables 4 and 5 show all treatments attempted and their percentage success.

Discussion

The sociodemographic profile of the subjects mirrors those found in previous studies, being predominately female, aged between the third and fifth decades, with a decreasing incidence with age.17,18,19,20,21 The level of social deprivation within our sample is also supported by the literature.22,23 Aggarwal22 found that subjects in the most deprived areas are 1.5 times more likely to report orofacial pain symptoms than those living in affluent areas, though the mechanism as to why this is the case remains unconfirmed. TMD, in some form, made up the vast majority (75%) of all orofacial pain cases in this cohort, which again is consistent with the literature24,25,26

Of the 76 cases of TMD in the sample, the majority (64%) had no specific descriptive subgroup diagnosis in their hospital records and were given the diagnosis of 'TMD' alone. Despite the lack of specificity of their diagnosis, there were successful conservative management strategies employed for a large proportion of these individuals. If conservative therapy fails, however, and there is no clear subgroup diagnosis, clinicians might attempt inappropriately targeted further treatment. Further to this if there is no clear subgroup diagnosis and therefore the patient's complaint can't be accurately attributed to an area (for example, joint, disc or muscle) then explanations given to the patients may not make sense and consequently confuse or cause stress to the patients. Studies have shown that using TMD as an all inclusive diagnosis, both clinically and as a research term, makes findings difficult to interpret, as differing pain causes are grouped and treated collectively. One author even suggests TMD should be completely removed from the diagnostic vocabulary on this basis.27

Confusion in the diagnosis and management of TMDs within the primary care setting are well documented.5,7 This audit, however, suggests that within specialist settings the research diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular disorders (RDC/TMD) is similarly not being utilised and that diagnostic ambiguity persists. This may be because clinically, regardless of a specific diagnosis, the same conservative management strategies are utilised for most TMD patients or because many patients' symptoms are sub-clinical with respect to the RDC/TMD.5 The lack of use of the RDC/TMD may also be attributable to a lack of familiarity and a perception that it is overly complex or time-consuming, as it was specifically designed to provide highly specific research diagnoses.5 With repeated use and familiarity this is not the case, as the trialling of alternative diagnostic tools has shown, but shorter diagnostic protocols are available (Clinical Examination Protocol-TMD [CEP-TMD]) and comparable to the gold standard of the RDC/TMD.5

Thirty-four subjects from the sample had experienced repeated imaging of their jaw joints using ionising investigations such as DPT and CT head. A DPT generates 0.007-0.026 mSv effective radiation dose28,29 and a CT head generates 2.0 mSv effective radiation dose.28,29 Although these individual doses of medical and dental diagnostic radiation are relatively small, cumulative and stochastic effects must be considered, as should dose utilisation.28,29 Both guidelines30,31,32 and regulations33,34 relating to ionising investigations state that justification and optimisation of investigations is mandatory. If the DPTs were ordered to examine purely the TMJ then they are difficult to justify, as current evidence suggests that they will not affect treatment planning.17,25,29 The finding that there is increased utilisation of radiography in our subjects is similar to the findings of Elrasheed et al.,3 who identified that oral medicine and maxillofacial surgery employed these investigations more routinely in facial pain cases compared to medical specialties treating the same condition. The inference made by Elrasheed et al.3 was that medical specialties typically only used radiographs when the patients' symptoms indicate the need and not as a routine screen. Clearly within our sample, unless new signs or symptoms have arisen, more use needs to be made of previous investigations.

The vast majority of the cohort (51%) appeared to have been referred from the primary care setting without mention of any treatment that had been attempted for their chronic orofacial pain condition. It may be that the primary care practitioners have omitted to include this information on their referral, however, given the prevalence of omission it is unlikely that this is the case for such a large proportion of our cohort.

The American Association of Dental Research strongly recommends that unless there is a justifiable reason to the contrary that conservative, reversible management strategies should be employed for TMDs.35 The fact that the most successful treatments undertaken by the oral and maxillofacial department were simple, common reversible management strategies seems to suggest that with adequate support and remuneration for the practitioner, a large proportion of subjects could have been managed in the primary care setting.5,7,36 Work from Wassell et al20 work supports this suggestion with four out of five patients with TMD successfully managed in primary dental care, using reversible conservative treatments (splints). Some clinicians feel, however, that using splints as a routine treatment modality for all facial pain patients is wrong,37 with patients potentially becoming reliant on splints or becoming hyper vigilant. Given their success38 and simple nature and the absence of data showing actual harm caused by using soft splints as a provisional treatment, we would suggest that for a patient whom the primary care practitioner has made a provisional diagnosis of a TMD, a soft splint remains a reasonable treatment option. Soft splints are not, however, appropriate for management of other forms of facial pain.

No management strategies have been proven in the literature to be uniformly effective in the treatment of chronic orofacial pain conditions. Given this lack of evidence it is unsurprising that we found multiple different modalities employed with limited clinical success. In addition, with the patients assessed in this paper, multiple referrals to differing medical and dental specialties could be a reason for the number of poor outcomes to management attempts and also the repeated investigations. Historically studies have shown that many patients undergo unnecessary dental treatments, such as irreversible dental extractions, in the mistaken view that the cause of pain is dental.4 Unfortunately this study found evidence to support this notion with 72% of extractions completed across all care settings having no impact on the subject's orofacial pain condition.

Many clinicians believe that for any management of chronic orofacial pain conditions to be successful, detailed discussion and education about the condition, reassurance that the conditions are in the most benign and self-limiting chronic conditions, is vital.4,17 If this discussion for the simpler cases could be done at the initial point of contact (primary care) this would likely both improve patient outcomes and facilitate specialist centres to focus on the more complex cases. In order for this to occur we, as have others,36 would suggest that targeted programmes of undergraduate and postgraduate education in chronic orofacial pain need to be established. In addition to this, appropriate support and remuneration of primary care practitioners should be provided for delivering education, advice and reassurance for patients suffering from chronic orofacial pain conditions.

By collecting the data from a hospital setting, this population represents cases which have been referred from the primary care setting. It has been shown that these cases usually represent more severe or intractable cases and thus the population studied is unlikely to be representative of all types of orofacial pain cases.21 Difficulty with coding of individuals suffering with chronic orofacial pain in primary dental practices was highlighted by the Steele report.39 Due to this we felt that we could not accurately retrospectively identify patients managed solely in the primary care setting and thus such patients are not represented in this paper. Similarly this paper does not show details of successful treatments completed by any specialty apart from OMFS and is likely to represent an overly negative and skewed cohort when compared to the general clinical population. In addition, all of the data reported in this study rely on the accuracy of the notes and referral letters for the patients included.

Bias may also have been introduced by the single examiner, (EVB) as it was their subjective opinion after reviewing the patient's hospital records, which graded treatment outcome from the information gathered in the notes. The single examiner was, however, a junior member of hospital staff and so it could be argued that being relatively untrained in this specialist field they were able to possess less bias as they had fewer preconceptions and less invested in the field.

Conclusion

There are a number of clinical issues raised by this study that require consideration. Primary care practitioners require education in how to diagnose and provide initial management of chronic orofacial pain. National initiatives to produce standardised chronic pain management protocols, such as the ongoing map of medicine project, would help provide a framework for all practitioners (specialist or non-specialist), empowering them and giving them confidence in primary management of chronic orofacial pain. Further to this, nationally standardised clear-cut care pathways for patients with chronic orofacial pain need to be established in order to reduce multiple re-referrals and improve efficiency and ultimately potentially the efficacy of care provided. The implementation of such national initiatives is essential to facilitate effective management of chronic orofacial pain at initial point of contact within the healthcare system irrespective of care setting.

The creation of specialist regional centres for chronic orofacial pain that is more complex to diagnose or manage should also be considered. Such regional centres could gather relevant multidisciplinary expertise in a single place, driving evidence-based practice and saving multiple re-referrals with their concomitant effects.

Finally investigation use, particularly those utilising ionising radiation, in chronic orofacial pain subjects should be carefully scrutinised to ensure the investigation is appropriate, justified and not duplicating previous investigations.

References

Aggarwal V R, McBeth J, Zakrzewska J M, Macfarlane G J . Unexplained orofacial pain – is an early diagnosis possible? Br Dent J 2008; 205: E6.

Aggarwal V R, Macfarlane G J, Farragher T M, McBeth J . Risk factors for the onset of chronic oro-facial pain - results of the North Cheshire oro-facial pain prospective population study. Pain 2010; 149: 354–359.

Elrasheed A A, Worthington H V, Ariyaratnam S, Duxbury A J . Opinions of UK specialists about terminology, diagnosis and treatment of atypical facial pain: a survey. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2004; 42: 566–571.

Zakrzewska J M . Diagnosis and management of non-dental orofacial pain. Dent Update 2007; 34: 134–136, 138–139.

Hasanain F, Durham J, Moufti A, Steen I N, Wassell R W . Adapting the diagnostic definitions of the RDC/TMD to routine clinical practice: a feasibility study. J Dent 2009; 37: 955–962.

GaldOn M J, Durá E, Andreu Y, Ferrando M, Poveda R, Bagán J V . Multidimensional approach to the differences between muscular and articular tempromandibular patients: coping, distress and pain characteristics. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2006; 102: 40–46.

Durham J, Exley C, Wassall R Steele J G . 'Management is a black art' – professional ideologies with respect to tempromandibular disorders. Br Dent J 2007; 202: E29.

Aggarwal V R, Lovell K, Peters S, Javidi H, Joughin A, Goldthorpe J . Psychosocial interventions for the management of chronic orofacial pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011: CD008456.

Pfaffenrath V, Rath M, Pöllmann W, Keeser W . Atypical facial pain - application of the IHS criteria in a clinical sample. Cephalalgia 1993; 13: 84–88.

Van Selms M K, Lobbezoo F, Visscher C M, Naeije M . Myofacial temporomandibular disorder pain, parafunctions and psychological distress. J Oral Rehabil 2008; 35: 45–52.

Burris J L, Evans D R, Carlson C R . Psychological correlates of medical comorbidities in patients with temporomandibular disorders. J Am Dent Assoc 2010; 141: 22–31.

Durham J, Steele J G, Wassell R W, Exley C . Living with uncertainty: temporomandibular disorders. J Dent Res 2010; 89: 827–830.

Makeham M, Dovey S, Runciman W, Larizgoitia I . Methods and measures used in primary care patient safety research – results of literature review. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2008. Online article available at http://www.who.int/patientsafety/research/methods_measures/makeham_dovey_full.pdf (accessed February 2013).

NHS Bradford and Airedale. Glossary of terms - secondary care. Online definition available at http://www.bradford.nhs.uk/about-us/glossary-of-terms/#STU (accessed February 2013).

NHS Doncaster. Health encyclopedia - tertiary care. Online definition available at http://www.doncaster.nhs.uk/your-health/health-encyclopaedia/#STU (accessed February 2013).

Dworkin, S F, LeResche L . Research diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular disorders: review, criteria, examinations and specifications, critique. J Craniomandib Disord 1992; 6: 301–355.

Durham J . Temporomandibular disorders (TMD): an overview. Oral Surg 2008; 1: 60–68.

Aggarwal V R, McBeth J, Zakrzewska J M, Lunt M, Macfarlane G J . Are reports of mechanical dysfunction in chronic oro-facial pain related to somatisation? A population based study. Eur J Pain 2008; 12: 501–507.

Aaron L A, Turner J A, Manci L A, Sawchuk C N, Huggins K H, Truelove E L . Daily pain coping among patients with chronic temporomandibular disorder pain: an electronic diary study. J Orofac Pain 2006; 20: 125–137.

Wassell R W, Adams N, Kelly P J . Treatment of temporomandibular disorders by stabilising splints in general dental practice: results after initial treatment. Br Dent J 2004; 197: 35–41.

Aggarwal V R, McBeth J, Zakrzewska J M, Lunt M, Macfarlane G J . The epidemiology of chronic syndromes that are frequently unexplained: do they have common associated factors? Int J Epidemiol 2006; 35: 468–476.

Aggarwal V R, Macfarlane T V, Macfarlane G J . Why is pain more common among people living in areas of low socio-economic status? A population-based cross-sectional study. Br Dent J 2003; 194: 383–387.

Andersson H I, Ejlertsson G, Leden I, Rosenberg C . Chronic pain in a geographically defined general population: studies of differences in age, gender, social class and pain localization. Clin J Pain 1993; 9: 174–182.

Giannakopoulos N N, Keller L, Rammelsberg P, Kronmϋller K T, Schmitter M . Anxiety and depression in patients with chronic temporomandibular pain and in controls. J Dent 2010; 38: 369–376.

Lipton J A, Ship J A . Larach-Robinson D. Estimated prevalence and distribution of reported orofacial pain in the United States. J Am Dent Assoc 1993; 124: 115–121.

Epstein J B, Caldwell J, Black G . The utility of panoramic imaging of the temporomandibular joint in patients with temporomandibular disorders. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2001; 92: 236–239.

Laskin D M . Temporomandibular disorders: a term past its time? J Am Dent Assoc 2008; 139: 124–128.

Whaites E . Essentials of dental radiography and radiology. 3rd edn. London: Churchill Livingstone, 2002.

Brooks S L, Brand J W, Gibbs S J et al. Imaging of the temporomandibular joint – a position paper of the American Academy of Oral and Maxillofacial Radiology. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 1997; 83: 609–618.

National Radiological Protection Board. Guidance notes for dental practitioners on the safe use of x-ray equipment. London: Department of Health, 2001. Online article available at http://www.hpa.org.uk/webc/HPAwebFile/HPAweb_C/1194947310610 (accessed February 2013).

National Radiological Protection Board. Guidelines on the patient dose to promote optimisation of protection for diagnostic medical exposures: report of an advisory group on ionising radiation. London: Department of Health, 1999.

National Radiological Protection Board. Patient dose reduction in diagnostic radiology. London: Department of Health, 1990.

The ionising radiation (medical exposure) regulations 2000. HMSO, London, 2000. Online regulations available at http://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2000/1059/contents/made (accessed February 2013).

The ionising radiations regulations 1999. HMSO, London, 1999. Online regulations available at http://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/1999/3232/contents/made (accessed February 2013).

American Association of Dental Research. Management of patients with TMD's: a new 'standard of care'. AADR, 2003. Online information available at http://www.aadronline.org/i4a/pages/index.cfm?pageid=3465 (accessed February 2013).

Aggarwal V R, Joughin A, Zakrzewska J M, Crawford F J, Tickle M . Dentists' and specialists' knowledge of chronic orofacial pain: results from a continuing professional development survey. Prim Dent Care 2011; 18: 41–44.

Stohler C . Temporomandibular joint disorders-the view widens while therapies are constrained. J Orofac Pain 2007; 21: 261.

Truelove E, Huggins K H, Mancl L, Dworkin S F . The efficacy of traditional, low-cost and nonsplint therapies for temporomandibular disorder: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Dent Assoc 2006; 137: 1099–1107.

Department of Health. NHS dental services in England: an independent review led by Jimmy Steele. London: Department of Health, 2009.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed Paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Beecroft, E., Durham, J. & Thomson, P. Retrospective examination of the healthcare 'journey' of chronic orofacial pain patients referred to oral and maxillofacial surgery. Br Dent J 214, E12 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2013.221

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2013.221

This article is cited by

-

An artificial intelligence model for the radiographic diagnosis of osteoarthritis of the temporomandibular joint

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Newly graduated dentists’ knowledge of temporomandibular disorders compared to specialists in Saudi Arabia

BMC Oral Health (2020)

-

Referrals to a facial pain service

British Dental Journal (2016)

-

Diagnosis, medication, and surgical management for patients with trigeminal neuralgia: a qualitative study

Acta Neurochirurgica (2015)

-

Developing Effective and Efficient care pathways in chronic Pain: DEEP study protocol

BMC Oral Health (2014)