Abstract

Background

Benzodiazepines are frequently used medications in the elderly, in whom they are associated with an increased risk of falling, with sometimes dire consequences.

Objective

To estimate the impact of benzodiazepine-associated injurious falls in a population of elderly persons.

Method

A nested case-control study was conducted using data collected during 10 years of follow-up of the French PAQUID (Personnes Agées QUID) community-based cohort. The main outcome measure was the occurrence of an injurious fall, which was defined as a fall resulting in hospitalization, fracture, head trauma or death. Controls (3:1) were frequency-matched to cases. Benzodiazepine exposure was the use of benzodiazepines over the previous 2 weeks reported at the follow-up visit preceding the fall.

Results

Benzodiazepine use was significantly associated with the occurrence of injurious falls, with a significant interaction with age. The adjusted odds ratio for injurious falls in subjects exposed to benzodiazepines was 2.2 (95% CI 1.4, 3.4) in subjects aged ≥80 years and 1.3 (95% CI 0.9, 1.9) in subjects aged <80 years. The population attributable risk for injurious falls in subjects exposed to benzodiazepines was 28.1% (95% CI 16.7, 43.2) for subjects aged ≥80 years. The incidence of injurious falls in subjects aged ≥80 years exposed to benzodiazepines in the PAQUID cohort was 2.8/100 person-years. Over 9% of these falls were fatal. According to these results and to recent population estimates, benzodiazepine use could be held responsible for almost 20 000 injurious falls in subjects aged ≥80 years every year in France, and for nearly 1800 deaths.

Conclusion

Given the considerable morbidity and mortality associated with benzodiazepine use and the fact that existing good practice guidelines on benzodiazepines have not been effective in preventing their misuse (possibly because they have not been applied), new methods for limiting use of benzodiazepines in the elderly need to be found.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Benzodiazepines and congeners (zolpidem, zopiclone) are among the drugs most frequently used in the elderly.[1,2] They are mostly prescribed for sleep disorders, a highly prevalent disorder in the elderly population.[3] However, their demonstrable activity is short lived, generally not exceeding a few weeks.[4,5] In their meta-analysis published in 2000, Holbrook et al.[4] clearly pointed out that “None of the data extracted in this review support long-term use (i.e., longer than 2 weeks).” In 2005, Glass et al.[5] confirmed this statement and added that the benefit of benzodiazepine use seemed even lower in elderly subjects, with a higher risk of adverse drug reactions. This is clearly in disagreement with the usual use of benzodiazepines, most of which is long-term in elderly subjects. Evidence-based guidelines have been formulated to limit the duration of benzodiazepine prescription[6] but this goal does not seem to have been achieved, with therapy persisting for >2 years in almost 80% of benzodiazepine-treated elderly patients.[7,8]

Benzodiazepines offer only symptomatic relief for sleep disorders and cause dependency. Once started, there is little incentive to stop treatment with these drugs. In the absence of curative treatment, the underlying disease will usually persist. Furthermore, there is no penalty for not stopping benzodiazepine treatment, despite official recommendations. Since, in addition, benzodiazepines cause withdrawal symptoms, it is not surprising that a large number of elderly patients continue to use them long term.

Benzodiazepines may be injurious to the health of elderly patients.[5,9] Many studies have evaluated the association between benzodiazepine use and falls, injurious falls, falls requiring medical attention and hip fractures. Some found a significantly increased risk for benzodiazepine users[10–19] whereas others found no significant association,[20–25] leading to inconsistencies in the literature. Falls are a frequent and major cause of morbidity in the elderly but their numerous definitions do not always allow a clear perception of their consequences.[26–29] Only falls with serious consequences have a real impact from a public health point of view and can be considered as events of interest by patients and their families. Consequently, we decided to study the association between benzodiazepine use and the occurrence of injurious falls in the elderly and to estimate the impact of benzodiazepine use on injurious falls in the elderly in France.

Methods

Design and Setting

A nested case-control study was conducted using data collected during 10 years of follow-up of the PAQUID (Personnes Agées QUID) study. The PAQUID research programme is a community-based cohort designed to study functional and cerebral aging in people aged ≥65 years,[30] randomly selected from the electoral rolls of 75 districts of Gironde and Dordogne, two administrative areas of the Aquitaine region in south-western France. A total of 3777 subjects were included in this cohort in 1988–9.

Subjects who agreed to participate in the PAQUID study were interviewed at home by trained neuropsychologists at inclusion and at 3, 5, 8 and 10 years. The interview included sociodemographic items, past and present medical history (including neurosensory deficiencies) and a set of neuropsychological tests. Of all the subjects included in the PAQUID cohort, only those who were not confined to bed and who completed at least two consecutive follow-up evaluations were eligible for this nested case-control study focusing on injurious falls.

Case Ascertainment and Validation

Injurious falls were defined as falls causing hospitalization, fractures, head trauma or death. All reported events of hospitalization, fracture or head trauma were identified in the data collected at baseline and during follow-up. The report forms corresponding to these events were consulted in order to determine the circumstances and consequences of these events and to identify those attributable to falls. Death certificates were also examined to determine if some recorded death events had been attributed to falling.

Four index periods were defined for cases according to the time of occurrence of the fall in the cohort. The first corresponded to time elapsed from inclusion to the third-year follow-up, the second from the third to the fifth-year follow-up, the third from the fifth to the eighth-year follow-up and the last from the eighth to the tenth-year follow-up.

Definition and Selection of Controls

For each case, all subjects with no report of injurious falls from baseline to the end of the index period were considered as potential controls. Controls were frequency-matched for the index period, the administrative area of residence (Gironde, Dordogne) and vital status. Three controls per case were selected from all eligible controls by simple random sampling. Any given patient selected as a control during one index period could be selected to serve as a control for a later index period, provided that he or she remained in the study cohort and was therefore also at risk of becoming a case. Likewise, a patient serving as a control could subsequently become a case.[31–33]

Definition of Exposure

All benzodiazepines available in France between 1988 and 1999 were considered, that is, alprazolam, bromazepam, chlordiazepoxide, clobazam, clonazepam, clotiazepam, clorazepate, diazepam, estazolam, flunitrazepam, loflazepate, loprazolam, lorazepam, lormetazepam, nitrazepam, nordazepam, oxazepam, prazepam, temazepam, tofizopam and triazolam, as well as the related compounds zolpidem, alpidem (withdrawn from the French market in October 1993) and zopiclone, irrespective of their main authorized indications (insomnia, anxiety).

Drug use was assessed in face-to-face interviews using an ad hoc questionnaire administered by trained neuropsychologists who were unaware of the nested case-control study’s hypothesis. At each follow-up point, subjects or their usual caregiver were asked about prescribed and non-prescribed drugs regularly used during the past 2 weeks. Drug use was then validated by visual inspection of the patient’s medicine packs by the interviewer.

Benzodiazepine exposure was defined as use of any benzodiazepine at the beginning of the index period. It was not possible to determine the exact temporal relationship between an injurious fall and benzodiazepine use (i.e. onset, time of day, etc.). However, given that the duration of use within our study subjects was continuous, the chances of a false-positive association of benzodiazepines with injurious falls were assumed to be small. This hypothesis was supported by the results of previous studies estimating that the majority of benzodiazepine treatments initiated in elderly people, including this cohort, persist for >2 years.[7,8] Moreover, this definition implied anteriority of exposure to event.

Potential Confounders

The analysis considered the main known or suspected risk factors for falls or injurious falls[11,16–18,20,34–41] at the beginning of the index period. Covariates were age in years, gender (female vs male), marital status (single vs others), institutionalization, diagnosis of dementia, presence of a depressive symptomatology according to the Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale (CES-D) with thresholds adapted to the French population,[42] presence of a disability according to the Cumulative Disability Index,[43] presence of neurosensory deficiencies and presence of urinary incontinence. Uses of other psychotropic medications, treatments for neurological illness, antihypertensive drugs, vasodilators, histamine H1 receptor antagonists (antihistamines) and the total number of other drugs were also considered in the analysis.

All data (including those of exposure) were retrieved on a systematic prospective basis within the cohort framework, independently of this specific study.

Statistical Analysis

Characteristics of cases, controls and consequences of injurious falls were described using percentages for categorical variables, and means and standard deviations for continuous variables. The incidence of injurious falls in the PAQUID cohort was estimated using the person-year method. The association between benzodiazepine use and occurrence of injurious fall was assessed by multivariate logistic regression.[44] To estimate the association between benzodiazepine exposure and the occurrence of injurious falls, a complete model including all potential confounders and frequency-matching variables was fitted. Interactions between benzodiazepine exposure and age, gender, dementia and depressive symptomatology were assessed. The level of significance used for tests was 0.05.

Population attributable risks and 95% confidence intervals were estimated by a method based on unconditional logistic regression. This method provides adjusted population attributable risk estimates by combining adjusted odds ratio (OR) estimates and the observed prevalence of the risk factors among cases.[45,46] Because the same logistic models are used to estimate both the OR and the population attributable risk, these measures are adjusted for the same risk factors in the same manner.

All analyses were conducted using SAS statistical software (version 8.02; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA), except population attributable risk analyses, which were performed using the Interactive Risk Assessment Program (IRAP v2.2).[47]

Results

Population

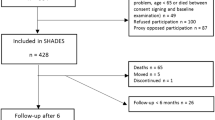

Among the 3777 subjects included in the PAQUID cohort, 840 were not eligible for the first index period, mainly because they had not completed the period and could not then be classified as cases or controls. The corresponding numbers were 124 subjects for the second index period, 122 subjects for the third period and 53 subjects for the last period. The study control sample and the complete PAQUID cohort population had similar distributions for gender and age at inclusion. Figure 1 shows the numbers of identified cases and selected controls for each index period.

During the 10 years of follow-up of the PAQUID cohort, 382 cases of injurious falls were identified, resulting in 275 hospitalizations (72.0% of injurious falls), 270 fractures (70.7%), 69 head injuries (18.1%) and 18 fatalities (4.7%).

Characteristics of cases and controls are presented in table I. Cases were more likely than controls to be women and single, and to have incapacities, visual deficiency, partial urinary incontinence and depressive symptoms. They were also slightly older. Cases used more medications than controls and were more likely to be exposed to all drug classes considered except for antihypertensive drugs. The prevalence of benzodiazepine use at the beginning of the index period was 45.8% among cases and 28.9% among controls. In subjects who did not die during the index period, the observed agreement for benzodiazepine exposure reported at the beginning and at the end of the index period was 83.6%. This agreement was 78.7% for cases and 85.2% for controls. Among cases and controls exposed at the beginning of the index period, 74.4% and 77.1%, respectively, were still exposed at the following visit. The Mac-Nemar test found no significant difference for exposure to benzodiazepines between the beginning and the end of the index period.

Multivariate Analyses

Benzodiazepine exposure was significantly associated with occurrence of injurious falls in the initial complete model (adjusted OR 1.7; 95% CI 1.3, 2.3), but a significant interaction between benzodiazepine use and age was found in this model (p = 0.007). As the mean and median ages in our sample were close to 78 years, subjects were separated into those aged <80 years and those aged ≥80 years. After stratification for age, the OR for injurious falls for subjects exposed to benzodiazepines aged <80 years was 1.3 (95% CI 0.9, 1.9) compared with 2.2 (95% CI 1.4, 3.4) for those aged ≥80 years. Other studied interactions were not significant (benzodiazepine use and gender, benzodiazepine use and depressive symptomatology, benzodiazepine use and dementia).

Multivariate analysis (table II) showed that the risk of falling in subjects aged <80 years was associated with female gender (OR 2.1; 95% CI 1.34, 3.13), use of antihistamines (OR 3.7; 95% CI 1.13, 12.25) and number of drugs used. In subjects aged ≥80 years, injurious falls were associated, in addition to benzodiazepines, with female gender (OR 2.4; 95% CI 1.42, 4.21) and use of vasodilators (OR 1.6; 95% CI 1.05, 2.41). Use of antihypertensive drugs was associated with a lower risk of injurious falls in these subjects (OR 0.6; 95% CI 0.4, 0.96). No significant association with other drug classes was found.

The population attributable risk of benzodiazepine use on injurious falls in subjects aged ≥80 years was estimated using an age-stratified model as 28.1% (95% CI 16.7, 43.2). This risk was not estimated in subjects aged <80 years because the OR of injurious falls for subjects exposed to benzodiazepines was not significantly different from one.

Sensitivity Analysis

We tested the potential bias induced by our definition of benzodiazepine exposure by substituting other definitions for this exposure. Subjects were considered fully exposed to benzodiazepines when they declared exposure both at the beginning and at the end of their index period. They were considered as only partly exposed if they declared exposure to benzodiazepines either at the beginning or at the end of their index period. Finally, subjects who declared no exposure to benzodiazepines at the beginning and at the end of their index period were considered as totally unexposed. Using these definitions of exposure did not change the adjusted OR for falls in subjects fully exposed to benzodiazepines, irrespective of whether they were <80 or ≥80 years of age.

Incidence of Injurious Falls Potentially Related to Benzodiazepine Exposure

Among subjects aged ≥80 years at the beginning of their index period, we identified 190 events of injurious falls, for an estimated incidence of 2.8/100 person-years. All fatal falls in the study involved subjects aged ≥80 years, representing 9.5% of falls in this age group.

Since >2 500 000 subjects would be aged ≥80 years in France according to recent population estimates,[48] approximately 71 000 injurious falls would be expected every year in these subjects. Based on the population attributable risk we estimated, almost 20 000 of these injurious falls would be related to benzodiazepine use, and consequently nearly 1800 deaths yearly in France could be attributed to benzodiazepine-related injurious falls.

Discussion

We found a significant association between benzodiazepine use and the occurrence of injurious falls in subjects aged ≥80 years. Subjects aged <80 years had a nonsignificant risk increase (1.3-fold) for injurious falls when exposed to benzodiazepines. Those aged ≥80 years were at higher risk, with a 2.2-fold increased risk. In this age group, it can be estimated that 28.1% (95% CI 16.7, 43.2) of injurious falls are related to the use of benzodiazepines. This represents almost 20 000 injurious falls every year in France, 9.5% of which are fatal.

These results are consistent with those reported in the literature concerning benzodiazepine exposure and falls or injurious falls in elderly people. Studies finding significant associations were more likely to include older subjects[11,12,14,15,41] whereas studies reporting insignificant results were more likely to consider younger populations.[20,21,23,34,49]

The distribution of gender and age at inclusion in our sample was similar to that of the overall PAQUID cohort, which is itself representative of the elderly population of the area.[30] The prevalences of benzodiazepine use and dementia in controls were also consistent with estimations made in the PAQUID study, and with those of another study of benzodiazepines and hip fracture in the same region.[22] These findings probably exclude the possibility of a major selection bias in the current study.

Collection of data was prospective (exposure and events), thereby minimizing recall and classification biases. Some minor falls may have been missed, but it is likely that none or few injurious falls, which were the focus of this study, were missed. Potential misclassifications would have biased OR estimates towards the null. Therefore, our findings are a conservative estimate of the association between benzodiazepine exposure and the occurrence of injurious falls.

Other definitions of falls as events of interest can be found in the literature. Some are not specific for injurious falls, and therefore did not seem relevant in terms of a public health impact because they may result in inclusion of events with limited consequences (e.g. superficial wounds). Conversely, other definitions defined severity only in terms of fractures and therefore seemed too restrictive, as severity might be better explored by paying attention also to head trauma and death.

Exposure was measured at the beginning of the index period. Because of the difficulty of stopping benzodiazepines and the very long duration of treatment, it was presumed that exposed subjects would not have stopped their drug intake between the time of exposure measurement and the time of event occurrence. In subjects who had not died during the index period, the observed agreement between benzodiazepine exposure reported at the beginning of the index period and benzodiazepine exposure reported at the end of the index period was 83.6%. Exposure to benzodiazepines was not significantly different at the beginning and at the end of the index period. Sensitivity analyses considering both ends of the index period for benzodiazepine exposure yielded results similar to those obtained in the main analyses.

Analyses were adjusted for known and important potential confounders (i.e. age, gender, drug intake, visual deficiency, incapacity, etc.). Nevertheless, we could not take into account several risk factors such as orthostatic hypotension/dizziness, gait and balance issues or neurological diseases, all of which are strongly related to falls.[50,51] The adjustment for medical treatment we performed may have compensated for this, as medical treatments can be considered proxies of the illness they are used for (for instance, adjusting for anti-Parkinson drug use could control for the existence of Parkinson disease).

Interestingly, our study indicated that the risk of falling in subjects aged <80 years was high in patients taking antihistamines (OR 3.7; 95% CI 1.13, 12.25). However, this association should be interpreted cautiously, given the very large confidence interval of the OR, and needs further investigation.

Indication bias could not be eliminated because the indications for medication use were not recorded in the data. Nevertheless, evidence of an association between the existence of sleep disorders and an increased risk of falls is rather weak in the literature. We performed a PubMed search using the keywords ‘sleep disorders’ and ‘injurious falls’ and found only two references.[52,53] In these two studies, while a significant association between sleep disorders and the occurrence of falls was found, the presence of medical treatments was not taken into account.

Our estimation of the association between benzodiazepine exposure and injurious falls in the elderly appears to be reasonably unbiased (although we could not adjust for the strength of benzodiazepine dose prescribed) and is consistent with what is known of the risks associated with benzodiazepines. Other major causality criteria were fulfilled in this study (significant association, precedence of exposure, consistency with literature and biological plausibility). Therefore, the estimation of impact indicators as a population attributable risk appears to be legitimate.

Our results, when extrapolated to the French population, indicate a considerable health burden on society in terms of injurious falls (hospitalizations, fractures, deaths), with almost 1800 deaths per year. These outcomes contrast, especially when the drugs are taken for long periods, with the small potential benefits of benzodiazepines, which after all are used for the symptomatic treatment of non-fatal disorders.[4] In addition, the demonstrated benefits of benzodiazepines are short lived, whereas their risks persist for as long as they are used, which is often for life, especially in the elderly.[4,5] Recommendations and restrictions have been put into effect in some countries: in France, prescription of benzodiazepines is limited to 4 weeks for insomnia and 12 weeks for anxiety. Obviously these restrictions have not been effective: in the current cohort, the best predictor of use of the drug at the end of an index period was its use at the beginning of a period lasting ≥2 years. In another nationwide study we found that in subjects aged >65 years, more than 80% had been using benzodiazepines for >6 months,[7] findings that are reproduced throughout the world in every study of benzodiazepine usage.[54–57] Moreover, a benzodiazepine in the elderly is often one of many drugs being taken and some patients may have major drug-drug interactions with benzodiazepines that put them at an increased risk for injurious falls and an increased risk of adverse events from other drugs.[58]

The prevalence of benzodiazepine use is particularly high in France, ranging from 25% to 30% in people aged ≥65 years,[7,8] a higher rate than that reported in other countries.[11,59] This high prevalence could be related to poor mental health or to poor health in general. However, several indicators tend to demonstrate that elderly French persons are actually in good health, with a long life expectancy, relatively low cardiovascular morbidity and low incapacity.[60,61] The prevalence or severity of anxious symptoms requiring anxiolytic treatment in the elderly also appears unlikely to explain this higher level of consumption.[7,8]

The numbers of elderly persons aged ≥80 years is increasing rapidly in Western countries, with recent estimates of almost 10.5 million persons aged ≥80 years in the US, over 2.6 million in the UK and about 1.1 million in Canada. Given that the prevalence of benzodiazepine use in elderly people in these countries ranges from 10% to 25% according to different estimates, the problem of benzodiazepine use in the elderly clearly does not appear to be restricted to France.

Conclusion

The results of this study show that there is a marked discrepancy between the limited benefits of benzodiazepines and their clear individual risks and public health costs. Perhaps their place in the market should be reconsidered. Certainly, any non-lifesaving drug associated with several thousand deaths yearly should be carefully re-evaluated and its use better monitored and controlled. Given the considerable morbidity and mortality associated with benzodiazepine use, and the fact that existing good practice guidelines on benzodiazepines have not been effective in preventing misuse (possibly because they are not applied), new methods need to be found to limit use of benzodiazepines in the elderly.

References

Nowell PD, Mazumdar S, Buysse DJ, et al. Benzodiazepines and zolpidem for chronic insomnia: a meta-analysis of treatment efficacy. JAMA 1997 Dec 24–31; 278(24): 2170–7

Shorr RI, Robin DW. Rational use of benzodiazepines in the elderly. Drugs Aging 1994 Jan; 4(1): 9–20

Corman B, Leger D. Sleep disorders in elderly. Rev Prat 2004 Jun 30; 54(12): 1281–5

Holbrook AM, Crowther R, Lotter A, et al. Meta-analysis of benzodiazepine use in the treatment of insomnia. CMAJ 2000 Jan 25; 162(2): 225–33

Glass J, Lanctot KL, Herrmann N, et al. Sedative hypnotics in older people with insomnia: meta-analysis of risks and benefits. BMJ 2005 Nov 19; 331(7526): 1169–75

Agence Française de Securite Sanitaire des Produits de Sante (AFSSaPS). Références médicales opposables n∘4. Prescription des hypnotiques et des anxiolytiques [online]. Available from URL: http://agmed.sante.gouv.fr/htm/5/5200c.htm#4.anxio/ [Accessed 2007 Nov 14]

Lagnaoui R, Depont F, Fourrier A, et al. Patterns and correlates of benzodiazepine use in the French general population. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2004 Sep; 60(7): 523–9

Lechevallier N, Fourrier A, Berr C. Benzodiazepine use in the elderly: the EVA Study. Rev Epidemiol Sante Publique 2003 Jun; 51(3): 317–26

Conn DK, Madan R. Use of sleep-promoting medications in nursing home residents: risks versus benefits. Drugs Aging 2006; 23(4): 271–87

Ensrud KE, Blackwell TL, Mangione CM, et al. Central nervous system-active medications and risk for falls in older women. J Am Geriatr Soc 2002 Oct; 50(10): 1629–37

Tromp AM, Pluijm SM, Smit JH, et al. Fall-risk screening test: a prospective study on predictors for falls in community-dwelling elderly. J Clin Epidemiol 2001 Aug; 54(8): 837–44

Herings RM, Stricker BH, de Boer A, et al. Benzodiazepines and the risk of falling leading to femur fractures: dosage more important than elimination half-life. Arch Intern Med 1995 Sep 11; 155(16): 1801–7

Lichtenstein MJ, Griffin MR, Cornell JE, et al. Risk factors for hip fractures occurring in the hospital. Am J Epidemiol 1994 Nov 1; 140(9): 830–8

Mustard CA, Mayer T. Case-control study of exposure to medication and the risk of injurious falls requiring hospitalization among nursing home residents. Am J Epidemiol 1997 Apr 15; 145(8): 738–45

Panneman MJ, Goettsch WG, Kramarz P, et al. The costs of benzodiazepine-associated hospital-treated fall injuries in the EU: a Pharmo study. Drugs Aging 2003; 20(11): 833–9

French DD, Werner DC, Campbell RR, et al. A multivariate fall risk assessment model for VHA nursing homes using the minimum data set. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2007 Feb; 8(2): 115–22

Koski K, Luukinen H, Laippala P, et al. Risk factors for major injurious falls among the home-dwelling elderly by functional abilities: a prospective population-based study. Gerontology 1998; 44(4): 232–8

Koski K, Luukinen H, Laippala P, et al. Physiological factors and medications as predictors of injurious falls by elderly people: a prospective population-based study. Age Ageing 1996 Jan; 25(1): 29–38

Souchet E, Lapeyre-Mestre M, Montastruc JL. Drug related falls: a study in the French Pharmacovigilance database. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2005 Jan; 14(1): 11–6

Kelly KD, Pickett W, Yiannakoulias N, et al. Medication use and falls in community-dwelling older persons. Age Ageing 2003 Sep; 32(5): 503–9

Lawlor DA, Patel R, Ebrahim S. Association between falls in elderly women and chronic diseases and drug use: cross sectional study. BMJ 2003 Sep 27; 327(7417): 712–7

Pierfitte C, Macouillard G, Thicoipe M, et al. Benzodiazepines and hip fractures in elderly people: case-control study. BMJ 2001 Mar 24; 322(7288): 704–8

de Rekeneire N, Visser M, Peila R, et al. Is a fall just a fall: correlates of falling in healthy older persons. The Health, Aging and Body Composition Study. J Am Geriatr Soc 2003 Jun; 51(6): 841–6

Ensrud KE, Blackwell T, Mangione CM, et al. Central nervous system active medications and risk for fractures in older women. Arch Intern Med 2003 Apr 28; 163(8): 949–57

Kron M, Loy S, Sturm E, et al. Risk indicators for falls in institutionalized frail elderly. Am J Epidemiol 2003 Oct 1; 158(7): 645–53

Tinetti ME, Doucette J, Claus E, et al. Risk factors for serious injury during falls by older persons in the community. J Am Geriatr Soc 1995 Nov; 43(11): 1214–21

Dargent-Molina P, Favier F, Grandjean H, et al. Fall-related factors and risk of hip fracture: the EPIDOS prospective study. Lancet 1996 Jul 20; 348(9021): 145–9

Kannus P, Niemi S, Palvanen M, et al. Fall-induced injuries among elderly people. Lancet 1997 Oct 18; 350(9085): 1174

Luukinen H, Koski K, Honkanen R, et al. Incidence of injurycausing falls among older adults by place of residence: a population-based study. J Am Geriatr Soc 1995 Aug; 43(8): 871–6

Dartigues JF, Gagnon M, Barberger-Gateau P, et al. The Paquid epidemiological program on brain ageing. Neuroepidemiology 1992; 11Suppl. 1: 14–8

Wacholder S, McLaughlin JK, Silverman DT, et al. Selection of controls in case-control studies: I. Principles. Am J Epidemiol 1992 May 1; 135(9): 1019–28

Wacholder S, Silverman DT, McLaughlin JK, et al. Selection of controls in case-control studies: III. Design options. Am J Epidemiol 1992 May 1; 135(9): 1042–50

Wacholder S, Silverman DT, McLaughlin JK, et al. Selection of controls in case-control studies: II. Types of controls. Am J Epidemiol 1992 May 1; 135(9): 1029–41

Blake AJ, Morgan K, Bendall MJ, et al. Falls by elderly people at home: prevalence and associated factors. Age Ageing 1988 Nov; 17(6): 365–72

Campbell AJ, Spears GF. Fallers and non-fallers. Age Ageing 1990 Sep; 19(5): 345–6

Graafmans WC, Ooms ME, Hofstee HM, et al. Falls in the elderly: a prospective study of risk factors and risk profiles. Am J Epidemiol 1996 Jun 1; 143(11): 1129–36

Leipzig RM, Cumming RG, Tinetti ME. Drugs and falls in older people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. II. Cardiac and analgesic drugs. J Am Geriatr Soc 1999 Jan; 47(1): 40–50

Luukinen H, Koski K, Laippala P, et al. Predictors for recurrent falls among the home-dwelling elderly. Scand J Prim Health Care 1995 Dec; 13(4): 294–9

Prudham D, Evans JG. Factors associated with falls in the elderly: a community study. Age Ageing 1981 Aug; 10(3): 141–6

Robbins AS, Rubenstein LZ, Josephson KR, et al. Predictors of falls among elderly people: results of two population-based studies. Arch Intern Med 1989 Jul; 149(7): 1628–33

van Doom C, Gruber-Baldini AL, Zimmerman S, et al. Dementia as a risk factor for falls and fall injuries among nursing home residents. J Am Geriatr Soc 2003 Sep; 51(9): 1213–8

Fuhrer R, Rouillon F. La version française de l’échelle CES-D (Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale): description et traduction de l’échelle d’autoévaluation. Psychiatry Psychobiol 1989; 4: 163–6

Barberger-Gateau P, Rainville C, Letenneur L, et al. A hierarchical model of domains of disablement in the elderly: a longitudinal approach. Disabil Rehabil 2000 May 10; 22(7): 308–17

Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. Applied logistic regression: textbook and solutions manual. 2nd ed. New York: John Wiley & Sons Inc., 1989

Benichou J, Gail MH. Estimates of absolute cause-specific risk in cohort studies. Biometrics 1990 Sep; 46(3): 813–26

Bruzzi P, Green SB, Byar DP, et al. Estimating the population attributable risk for multiple risk factors using case-control data. Am J Epidemiol 1985 Nov; 122(5): 904–14

National Cancer Institute. Interactive risk attributable program (IRAP v2.2) [online]. Available from URL: http://dceg.cancer.gov/tools/analysis/irap/ [Accessed 2007 Nov 14]

Brutel C, Omalek L. Projections demographiques pour la France, ses regions et ses departements (horizon 2030–2050) [online]. Available from URL: http://www.insee.fr/fr/ffc/docs_ffc/irsoc016.pdf [Accessed 2007 Nov 14]

Lord SR, Ward JA, Williams P, et al. Physiological factors associated with falls in older community-dwelling women. J Am Geriatr Soc 1994 Oct; 42(10): 1110–7

Bloem BR, Grimbergen YA, Cramer M, et al. Prospective assessment of falls in Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol 2001 Nov; 248(11): 950–8

Montero-Odasso M, Schapira M, Duque G, et al. Gait disorders are associated with non-cardiovascular falls in elderly people: a preliminary study. BMC Geriatr 2005; 5: 15

Brassington GS, King AC, Bliwise DL. Sleep problems as a risk factor for falls in a sample of community-dwelling adults aged 64–99 years. J Am Geriatr Soc 2000 Oct; 48(10): 1234–40

Latimer Hill E, Cumming RG, Lewis R, et al. Sleep disturbances and falls in older people. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2007 Jan; 62(1): 62–6

Gray SL, Eggen AE, Blough D, et al. Benzodiazepine use in older adults enrolled in a health maintenance organization. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2003 Sep–Oct; 11(5): 568–76

Jorm AF, Grayson D, Creasey H, et al. Long-term benzodiazepine use by elderly people living in the community. Aust N Z J Public Health 2000 Feb; 24(1): 7–10

Valenstein M, Taylor KK, Austin K, et al. Benzodiazepine use among depressed patients treated in mental health settings. Am J Psychiatry 2004 Apr; 161(4): 654–61

Zarifian E. Prescription of psychotropic drugs; use, misuse and abuse. Bull Acad Natl Med 1998; 182(7): 1439–46; discussion 46–7

French DD, Chirikos TN, Spehar A, et al. Effect of concomitant use of benzodiazepines and other drugs on the risk of injury in a veterans population. Drug Saf 2005; 28(12): 1141–50

Gray SL, Penninx BW, Blough DK, et al. Benzodiazepine use and physical performance in community-dwelling older women. J Am Geriatr Soc 2003 Nov; 51(11): 1563–70

Ankri J. Dependance du sujet age: quels chiffres? Rev Prat 2001; 15: 1623–6

Tunstall-Pedoe H, Kuulasmaa K, Mahonen M, et al. Contribution of trends in survival and coronary-event rates to changes in coronary heart disease mortality: 10-year results from 37 WHO MONICA project populations. Monitoring trends and determinants in cardiovascular disease. Lancet 1999 May 8; 353(9164): 1547–57

Acknowledgements

The PAQUID project was funded by: Caisse Nationale d’Assurance Maladie des Travailleurs Salariés (CNAMTS), Conseil Général de la Dordogne, Conseil Général de la Gironde, Conseil Régional d’Aquitaine Fondation de France, France Alzheimer (Paris), Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale (INSERM) Groupement d’Intérêt Scientifique (GIS) Longévité, Mutuelle Générale de l’Education Nationale (MGEN), Mutualité Sociale Agricole (MSA) AGRICA, Novartis Pharma (France) and Scor Insurance (France).

The funding sources had no role in the design and conduct of the study, no role in the collection, management, analysis and interpretation of the data and no role in the preparation, review and approval of the manuscript. The authors have no conflicts of interest that are directly relevant to the content of this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pariente, A., Dartigues, JF., Benichou, J. et al. Benzodiazepines and Injurious Falls in Community Dwelling Elders. Drugs Aging 25, 61–70 (2008). https://doi.org/10.2165/00002512-200825010-00007

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2165/00002512-200825010-00007