Abstract

OBJECTIVE: To assess the attitudes of practicing general internists toward evidence-based medicine (EBM—defined as the process of systematically finding, appraising, and using contemporaneous research findings as the basis for clinical decisions) and their perceived barriers to its use.

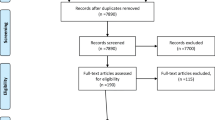

DESIGN: Cross-sectional, self-administered mail questionnaire conducted between June and October 1997.

SETTING: Canada.

PARTICIPANTS: Questionnaires were sent to all 521 physician members of the Canadian Society of Internal Medicine with Canadian mailing addresses; 296 (60%) of 495 eligible physicians responded. Exclusion of two incomplete surveys resulted in a final sample size of 294.

MAIN RESULTS: Mean age of respondents was 46 years, 80% were male, and 52% worked in large urban medical centers. Participants reported using EBM in their clinical practice always (33, 11%), often (173, 59%), sometimes (80, 27%), or rarely/never (8, 3%). There were no significant differences in demographics, training, or practice types or locales on univariate or multivariate analyses between those who reported using EBM often or always and those who did not. Both groups reported high usage of traditional (non-EBM) information sources: clinical experience (93%), review articles (73%), the opinion of colleagues (61%), and textbooks (45%). Only a minority used EBM-related information sources such as primary research studies (45%), clinical practice guidelines (27%), or Cochrane Collaboration Reviews (5%) on a regular basis. Barriers to the use of EBM cited by respondents included lack of relevant evidence (26%), newness of the concept (25%), impracticality for use in day-to-day practice (14%), and negative impact on traditional medical skills and “the art of medicine” (11%). Less than half of respondents were confident in basic skills of EBM such as conducting a literature search (46%) or evaluating the methodology of published studies (34%). However, respondents demonstrated a high level of interest in further education about these tasks.

CONCLUSIONS: The likelihood that physicians will incorporate EBM into their practice cannot be predicted by any demographic or practice-related factors. Even those physicians who are most enthusiastic about EBM rely more on traditional information sources than EBM-related sources. The most important barriers to increased use of EBM by practicing clinicians appear to be lack of knowledge and familiarity with the basic skills, rather than skepticism about the concept.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Rosenberg W, Donald A. Evidence based medicine: an approach to clinical problem-solving. BMJ. 1995;310:1122–6.

Sackett DL, Rosenberg WMC, Muir Gray JA, Haynes RB, Richardson WS. Evidence based medicine: what it is and what it isn’t. BMJ. 1996;312:71–2.

Shin JH, Haynes RB, Johnston ME. Effect of problem-based, selfdirected undergraduate education on life-long learning. Can Med Assoc J. 1993;148:969–76.

Bennett KJ, Sackett DL, Haynes RB, Neufeld VR. A controlled trial of teaching critical appraisal of the clinical literature to medical students. JAMA. 1987;257:2451–4.

Bordley DR, Fagan M, Theige D. Evidence-based medicine: a powerful educational tool for clerkship education. Am J Med. 1997;102:427–32.

Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. Evidence-based medicine: a new approach to teaching the practice of medicine. JAMA. 1992;268:2420–5.

Chalmers I, Dickersin K, Chalmers TC. Getting to grips with Archie Cochrane’s agenda. BMJ. 1992;305:786–7.

Hayward RSA, Guyatt GH, Moore KA, McKibbon KA, Carter AO. Canadian physicians’ attitudes about and preferences regarding clinical practice guidelines. Can Med Assoc J. 1997;156:1715–23.

McAlister FA. Influencing practice patterns in hypertension. Can Med Assoc J. 1997;157:1348–9. Letter.

Tunis SR, Hayward RSA, Wilson MC, et al. Internists’ attitudes about clinical practice guidelines. Ann Intern Med. 1994;120:956–63.

Naylor CD. Grey zones of clinical practice: some limits to evidencebased medicine. Lancet. 1995;345:840–2.

Haynes RB, Sackett DL, Guyatt GH, Cook DJ, Muir Gray JA. Transferring evidence from research into practice, 4: overcoming barriers to application. ACP J Club. 1997;126:A14–5.

Hayward RSA, Wilson MC, Tunis SR, Guyatt GH, Moore KA, Bass EB. Practice guidelines: what are internists looking for? J Gen Intern Med. 1996;11:176–8.

Smith R. What clinical information do doctors need? BMJ. 1996;313:1062–8.

Davis DA, Thomson MA, Oxman AD, Haynes RB. Changing physician performance: a systematic review of the effect of continuing medical education strategies. JAMA. 1995;274:700–5.

Slawson DC, Shaughnessy AF. Obtaining useful information from expert based sources. BMJ. 1997;314:947–9.

Weatherall DJ, Ledingham JGG, Warrell DA. On dinosaurs and medical textbooks. Lancet. 1995;346:4–5.

Antman EM, Lau J, Kupelnick B, Mosteller F, Chalmers TC. A comparison of results of meta-analyses of randomized control trials and recommendations of clinical experts: treatments for myocardial infarction. JAMA. 1992;268:240–8.

Mulrow CD. The medical review article: state of the science. Ann Intern Med. 1987;106:485–8.

Cook DJ, Griffith LE, Sackett DL. Importance of and satisfaction with work and professional interpersonal issues: a survey of physicians practising general internal medicine in Ontario. Can Med Assoc J. 1995;153:755–63.

McColl A, Smith H, White P, Field J. General practitioners’ perceptions of the route to evidence based medicine: a questionnaire survey. BMJ. 1998;316:361–5.

Olatunbosun OA, Edouard L, Pierson RA. Physicians’ attitudes toward evidence based obstetric practice: a questionnaire survey. BMJ. 1998;316:365–6.

Weingarten S, Stone E, Hayward R, et al. The adoption of preventive care practice guidelines by primary care physicians: do actions match intentions. J Gen Intern Med. 1995;10:138–44.

Covell DG, Uman GC, Manning PR. Information needs in office practice: are they being met? Ann Intern Med. 1985;103:596–9.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

This project was supported by an unrestricted grant from Bristol-Myers Squibb.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

McAlister, F.A., Graham, I., Karr, G.W. et al. Evidence-based medicine and the practicing clinician. J GEN INTERN MED 14, 236–242 (1999). https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.1999.00323.x

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.1999.00323.x