Abstract

Purpose

Smoking has declined in Canada in recent years. However, it is not clear whether differences in current smoking by socioeconomic status have increased, decreased, or remained unchanged in Canada.

Methods

We examined rates of current smoking by sex, education, and province from 1950 to 2011. Differences in current smoking, initiation, and cessation were summarized using relative and absolute measures.

Results

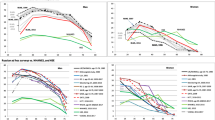

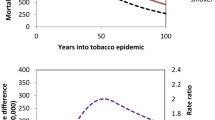

Between 1950 and 2011, the prevalence of current smoking (including daily and non-daily) among adults aged 20 years and older decreased steadily in men from 68.9 % (95 % CI 63.9–73.3) to 18.6 % (14.9–22.1) but in women increased slightly from 38.2 % (32.3–42.2) in 1950 to 39.1 % (36.4–41.2) in 1959 before declining to 15.4 % (11.9–18.9) in 2011. Among men, there was an inverse association between educational attainment and smoking which was consistent from 1950 to 2011. A similar gradient emerged in the mid-1960s in women. Absolute differences in rates of smoking across levels of education increased despite overall declines in smoking across all levels of education. Rates of smoking in women and men were higher in the Atlantic Provinces and Quebec, although in men these differences have declined since the 1990s. In a subset of data from 1999 to 2011, those with lower levels of education had higher levels of smoking initiation and lower levels of cessation.

Conclusions

Smoking rates have fallen over time but socioeconomic differences have increased. Smoking prevalence peaked later in lower socioeconomic status (SES) groups, and rates of decline in lower SES groups and certain provinces have been less steep. This suggests that SES gradients emerge rapidly in later stages of the tobacco epidemic and may have increased through greater efficacy of tobacco control policies in reducing smoking among those of higher SES compared to those of lower SES. Tailored approaches may be required to reduce smoking rates in those of lower SES and narrow SES differences.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The relative change in the ratio of smoking prevalence between low- and high-SES groups was calculated for each study as follows. First, SES ratios were defined for the first and final study years as the rates of smoking in low-SES groups divided by the rates in high-SES groups. Next, the relative change in the ratio was calculated as the difference in these ratios divided by the ratio in the first study year and expressed as a percentage. For example, in Barnett (first row of Table 1), the SES ratio was 1.9 in the final year and 1.6 in the first year, yielding a relative change in the ratio of (1.925–1.58)/1.58 = 21.8 %. Note ratios in the table have been rounded to 1 decimal place.

References

Pierce JP (1989) International comparisons of trends in cigarette smoking prevalence. Am J Public Health 79:152–157

Canada Health (2010) Canadian tobacco use monitoring survey (CTUMS): smoking prevalence 1999–2010. Health Canada, Controlled Substances and Tobacco Directorate, Ottawa

King B, Dube S, Kaufmann R, Shaw L, Pechacek T (2011) Vital signs: current cigarette smoking among adults aged ≥18 years–United States, 2005–2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 60:1207–12

Stephens M, Siroonian J (1998) Smoking prevalence, quit attempts and successes. Health Rep. 9: 31–37(Eng); -8(Fre)

Stephens T (1988) A critical review of Canadian survey data on tobacco use, attitudes and knowledge. Tobacco Programs Unit, Health Promotion Directorate, Health and Welfare Canada, Ottawa, ON

Canada Health (2010) Supplementary tables, CTUMS annual 2010 (February–December 2010). Health Canada, Controlled Substances and Tobacco Directorate, Ottawa, ON

Jarvis M, Wardle J (2006) Social patterning of individual health behaviours: the case of cigarette smoking. In: Marmot MG, Wilkinson RG (eds) Social determinants of health, 2nd edn. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Barbeau EM, Krieger N, Soobader MJ (2004) Working class matters: socioeconomic disadvantage, race/ethnicity, gender, and smoking in NHIS 2000. Am J Public Health 94:269–278

Huisman M, Kunst AE, Mackenbach JP (2005) Educational inequalities in smoking among men and women aged 16 years and older in 11 European countries. Tob Control 14:106–113

Lopez AD, Collishaw NE, Piha T (1994) A descriptive model of the cigarette epidemic in developed countries. Tob Control 3:242–247

Colman G, Remler D (2004) Vertical equity consequences of very high cigarette tax increases. National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA

Barnett R, Pearce J, Moon G (2009) Community inequality and smoking cessation in New Zealand, 1981–2006. Soc Sci Med 68:876–884

Office for National Statistics (ONS) (2001) Living in Britain: results from the 2000–1 general household survey. The Stationary Office, London

Graham H (1996) Smoking prevalence among women in the European community 1950–1990. Soc Sci Med 43:243–254

Garfinkel L (1997) Trends in cigarette smoking in the United States. Prev Med 26:447–450

Giskes K, Kunst AE, Benach J et al (2005) Trends in smoking behaviour between 1985 and 2000 in nine European countries by education. J Epidemiol Community Health 59:395–401

Hill SE, Blakely TA, Fawcett JM, Howden-Chapman P (2005) Could mainstream anti-smoking programs increase inequalities in tobacco use? New Zealand data from 1981–96. Aust N Z J Public Health 29:279–284

Kanjilal S, Gregg EW, Cheng YJ et al (2006) Socioeconomic status and trends in disparities in 4 major risk factors for cardiovascular disease among US adults, 1971–2002. Arch Intern Med 166:2348–2355

Lee DJ, LeBlanc W, Fleming LE, Gomez-Marin O, Pitman T (2004) Trends in US smoking rates in occupational groups: the National Health Interview Survey 1987–1994. J Occup Environ Med 46:538–548

Lee DS, Chiu M, Manuel DG et al (2009) Trends in risk factors for cardiovascular disease in Canada: temporal, socio-demographic and geographic factors. CMAJ 181:E55–E66

Millar WJ, Stephens T (1993) Social status and health risks in Canadian adults: 1985 and 1991. Health Rep 5:143–156

Najman JM, Toloo G, Siskind V (2006) Socioeconomic disadvantage and changes in health risk behaviours in Australia: 1989–90 to 2001. Bull World Health Organ 84:976–984

Smith P, Frank J, Mustard C (2009) Trends in educational inequalities in smoking and physical activity in Canada: 1974–2005. J Epidemiol Community Health 63:317–323

Harper S, Lynch J (2007) Selected comparisons of measures of health disparities: a review using databases relevant to healthy people 2010 cancer-related objectives. NCI cancer surveillance monograph series, Number 7. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute

Lund KE, Roenneberg A, Hafstad A (1995) The social and demographic diffusion of the tobacco epidemic in Norway. In: Slama K (ed) Tobacco and health. Plenum Press, New York, pp 565–571

Federico B, Kunst AE, Vannoni F, Damiani G, Costa G (2004) Trends in educational inequalities in smoking in northern, mid and southern Italy, 1980–2000. Prev Med 39:919–926

Osler M, Gerdes LU, Davidsen M et al (2000) Socioeconomic status and trends in risk factors for cardiovascular diseases in the Danish MONICA population, 1982–1992. J Epidemiol Community Health 54:108–113

Hiscock R, Bauld L, Amos A, Platt S (2012) Smoking and socioeconomic status in England: the rise of the never smoker and the disadvantaged smoker. J Public Health 34:390–396

Winkleby MA, Fortmann SP, Rockhill B (1992) Trends in cardiovascular disease risk factors by educational level: the Stanford Five-City Project. Prev Med 21:592–601

Corsi DJ, Lear SA, Chow CK, Subramanian SV, Boyle MH, Teo KK (2013) Socioeconomic and geographic patterning of smoking behaviour in Canada: a cross-sectional multilevel analysis. PLoS ONE 8:e57646

Reid JL, Hammond D, Burkhalter R, Ahmed R (2012) Tobacco use in Canada: patterns and trends, 2012th edn. Propel Centre for Population Health Impact, University of Waterloo, Waterloo, ON

Bains N (2009) Standardization of rates. Association of Public Health Epidemiologists in Ontario, Toronto, ON

Honaker J, King G, Blackwell M (2011) Amelia II: a program for missing data. J Stat Softw 47:1–47

Honaker J, King G (2010) What to do about missing values in time series cross-section data. Am J of Pol Sci 54:561–581

Tomz M, Wittenberg J, King G (2003) CLARIFY: software for interpreting and presenting statistical results. J Stat Softw 8:1–30

US Dept of Health and Human Services (1989) Reducing the health consequences of smoking: 25 years of progress. A report of the surgeon general. Rockville, MD: US Dept of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health

Cutler DM, Lleras-Muney A (2010) Understanding differences in health behaviors by education. J Health Econ 29:1–28

Clarke W (2000) 100 years of education. Can Soc Trends 59(Winter):3–7

Harper S, Lynch J (2005) Methods for measuring cancer disparities: using data relevant to healthy people 2010 cancer-related objectives. NCI cancer surveillance monograph series, number 6. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute

Hayes LJ, Berry G (2002) Sampling variability of the Kunst-Mackenbach relative index of inequality. J Epidemiol Community Health 56:762–765

Mackenbach JP, Kunst AE (1997) Measuring the magnitude of socio-economic inequalities in health: an overview of available measures illustrated with two examples from Europe. Soc Sci Med 44:757–771

Forey B (2002) International smoking statistics: a collection of historical data from 30 economically developed countries, 2nd edn. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Cornfield J, Haenszel W, Hammond EC, Lilienfeld AM, Shimkin MB, Wynder EL (2009) Smoking and lung cancer: recent evidence and a discussion of some questions. 1959. Int J Epidemiol 38:1175–1191

Omran AR (1971) The epidemiologic transition. A theory of the epidemiology of population change. Milbank Mem Fund Q 49:509–538

Corsi DJ, Chow CK, Lear SA, Subramanian SV, Teo KK, Boyle MH (2012) Smoking in context: a multilevel analysis of 49,088 communities in Canada. Am J Prev Med 43:601–610

Reid JL, Hammond D (2012) Tobacco use in Canada: patterns and trends, 2012 edition (supplement: tobacco control policies in Canada). Propel Centre for Population Health Impact, University of Waterloo, Waterloo, ON

Legleye S, Khlat M, Beck F, Peretti-Watel P (2011) Widening inequalities in smoking initiation and cessation patterns: a cohort and gender analysis in France. Drug Alcohol Depend 117:233–241

Frohlich KL, Potvin L (2008) Transcending the known in public health practice: the inequality paradox: the population approach and vulnerable populations. Am J Public Health 98:216–221

Acknowledgments

Part of the work presented in this paper was conducted by DJC while a doctoral student at McMaster University and the Population Health Research Institute (Hamilton, ON, Canada). The authors acknowledge the support of the McMaster University Research Data Centre for assistance with accessing the survey data files used in this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Corsi, D.J., Boyle, M.H., Lear, S.A. et al. Trends in smoking in Canada from 1950 to 2011: progression of the tobacco epidemic according to socioeconomic status and geography. Cancer Causes Control 25, 45–57 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-013-0307-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-013-0307-9